One mother brings personal experience to the new

National Center for Improving Literacy

Laura Shultz boating with her daughter, Catherine.

Laura Schultz is co-founder of Decoding Dyslexia Maryland and previously worked as a Congressional Staffer for Rep. Helen Delich Bentley and later as the Director of Federal and State Government Relations for a national trade association in Washington, D.C. She has a background in public policy and consulted for a Florida-based public relations firm for many years before “retiring” to focus on dyslexia advocacy to help children who struggle to read, write and spell in public school. She has two children, one a senior at Leonardtown High School and the other a junior at the U.S. Military Academy. Her husband is active duty Navy and they are a proud military family

Something was wrong, but no one could quite figure out what to call it.

At age three, my daughter Catherine spoke very few words compared to her brother. Early evaluations revealed that she needed speech and occupational therapy services.

Catherine displayed behavioral issues including aggression, which the school psychologist later attributed to possibly too much stimulation. At other times, she was withdrawn. She was held back in preschool because of these issues.

When she entered kindergarten, Catherine had meltdowns because of her frustrations with language.

What I saw was her having difficulty finding words and using incorrect language, which resulted in a scrambled output of the words she could find.

After three years in preschool and a year of kindergarten, she could not identify her letters and sounds, write her own name or spell simple words. I felt strongly that we were looking at a reading problem, and my advocacy finally resulted in her being found eligible for special education as a child with a “specific learning disability.”

As Catherine prepared to enter first grade at age seven, I was frightened and frustrated feeling that my child was in crisis and it did not seem that the district’s special education personnel knew how to address her reading and writing needs.

The years of pull-out services, small-group instruction and reading interventions produced few results.

Unfortunately it would take another six years from the time she was identified as having a “specific learning disability” before we understood her specific learning disability was dyslexia.

One year her teacher pulled me aside to share the Patricia Polacco book, “Thank you, Mr. Falker” and encouraged me to read it to Catherine. It was the first time anyone almost mentioned the common learning disability by name.

By fifth grade, our developmental pediatrician formally diagnosed Catherine with dyslexia. We shared the news with her school team hoping that we would finally be able to get the appropriate instruction in place for our daughter.

Unfortunately, we still found it difficult to bridge the divide between the evidence-based interventions being recommended and the programs and expertise available in our school.

By seventh grade, we had to move on to seek private reading and writing instruction for Catherine.

Through pinpointing Catherine’s dyslexia and getting her the proper services she needed, she is now a high school senior pursuing a certification in Computer Aided Design and Drawing (CADD), taking two English courses and making plans for college.

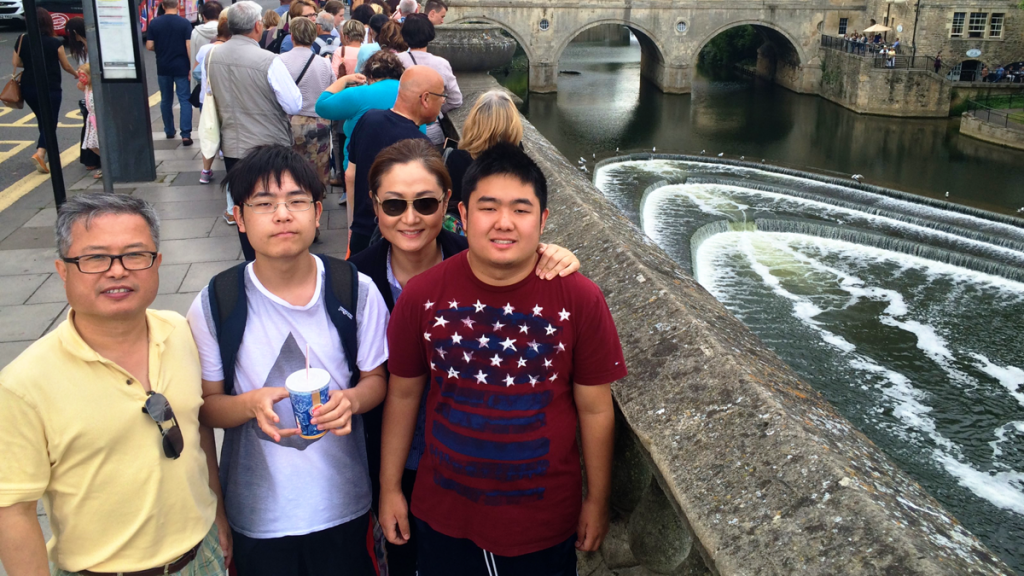

Laura Schultz and daughter, Catherine

Students like my daughter sit in every classroom in every school in every state. They are ethnically, culturally and socio-economically diverse. Many of these students will have access to the resources our family ultimately pursued and that is good, but truth be told, many more will not and that is a problem.

Unidentified dyslexia often creates social and emotional difficulties for struggling children. Parents’ and schools’ lack of understanding and awareness of dyslexia and other disabilities can exacerbate a child’s struggles unnecessarily. I knew other families and schools would benefit from knowing about early reading interventions that included phonological awareness and decoding instruction—this type of instruction would not only reduce the underlying cause of a child’s anxieties or challenging behaviors, but would also teach them to read.

My family’s experience, in what I would describe as an excellent public school system, motivated me to reach out to other parents of children with dyslexia. I knew that many of these families were experiencing similar situations and that collectively we may be able to raise awareness and bring much needed resources to our schools and communities.

We established Decoding Dyslexia Maryland, a parent-led grassroots movement that offers awareness, support and advocacy for children with dyslexia, their parents and educators.

Through my advocacy work with Decoding Dyslexia Maryland, I was asked to serve as a parent stakeholder on the Family Engagement Advisory Board for the National Center on Improving Literacy* (NCIL), which was funded by Office of Special Education Programs in September 2016.

NCIL is an important component of the U.S. Department of Education’s mandate under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) to support students with learning disabilities such as dyslexia. The center is tasked with:

- Developing and/or identifying tools to screen for and detect reading challenges early;

- Identifying evidence-based literacy instruction, strategies, accommodations and assistive technology;

- Providing information to support families;

- Developing and/or identifying professional development for teachers on early indicators and instructional strategies; and

- Disseminating these resources within existing federal networks.

Schools today are searching for information and assistance in implementing the evidence-based instruction outlined in ESSA and required by many of the new dyslexia laws passing in state legislatures across the country.

As I near the end of my family’s personal pre-K-12 journey, I’m excited to be able to offer NCIL the benefit of my daughter’s experiences to help change the way students with reading challenges and dyslexia are identified and taught to read.

It’s my expectation that NCIL, in collaboration with parents, educators, community partners, and reading researchers, will offer our public schools the information and guidance they need to bring the science of reading into their classrooms and to close the research-to-practice gap that sometimes hinders their ability to deliver best practices in literacy instruction to the students that need it the most.

This October, Learning Disabilities Awareness Month, is the perfect time to learn more about the mission of the NCIL and to spread the word to your schools and communities about dyslexia and this new research-based resource. Encourage teachers, principals and families to visit the NCIL website and make suggestions about the types of information, tools, trainings and resources that are most needed.

* The National Center on Improving Literacy is a partnership among literacy experts, university researchers, and technical assistance providers, with funding from the U.S. Department of Education.

Blog articles provide insights on the activities of schools, programs, grantees, and other education stakeholders to promote continuing discussion of educational innovation and reform. Articles do not endorse any educational product, service, curriculum or pedagogy.