“Something that empowers me as a Native student is just being able to know my culture and where I’m from, and just being able to have responsibilities over my culture.”

On Friday July 22nd, 2016, the White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education (WHIAIANE) and the Office of Indian Education (OIE) hosted the Pathkeepers Indigenous Knowledge Youth Leadership Camp for round table discussion on the importance of culture and representation in their education. Department staff heard from 31 students ages 11-18, representing nations across the country such as the Navajo Nation, Zuni Pueblo, Salt River Pima-Maricopa, Onondaga Nation, Hopi, Upper Mattaponi, Gila River, Confederated Salish & Kootenai, Blackfeet, Chippewa Cree, and San Felipe Pueblo just to name a few.

Ron Lessard, chief of staff of WHIAIANE, welcomed the group and Joyce Silverthorne provided an informational overview on the role of the OIE in their schools. The President of the Pathkeepers for Indigenous Knowledge program, Angelina Okuda-Jacobs, Lumbee, had prepped her students on school environment issues and the importance of culture, tradition, and Native languages. Okuda-Jacobs emphasized the importance of bringing youth from around the country together to engage them in the policy process early, to provide their valuable on-the-ground feedback, and to help them realize that they are not alone in the struggles or successes they may experience in their own communities.

Listening and sharing to build understanding

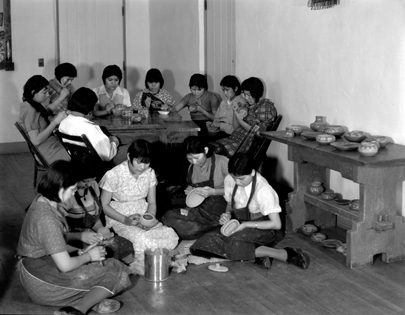

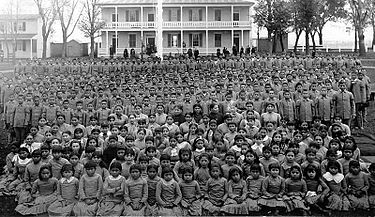

The students displayed a depth of understanding about stereotypical representation, historical trauma, and its modern effects in their own communities in a way that seemed wise beyond their young years. Discussion questions asked what their school environment and education meant to them. They shared stories of being the only Native student in their urban schools and being made to feel historical and fictional through the representations in the media and the way their classmates approached them.

When asked what their perfect school would have, students shared the idea of online learning where students can learn at their own pace and take prescriptive tests in the beginning of their units. Others touted a school day that started later in the morning, had more recess, and did project-based learning.

Space was provided for students to share their personal stories and experiences. One student shared their explicit goals to attend American University for political science and move on to law school at Arizona State University in order to advocate for their tribe. This ambition started as an example set by role models and attending a Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing when they were 7 years old. Others challenged visibility stereotypes and are changing the narrative on what the identity of being Native American means for someone who does not “look” the part.

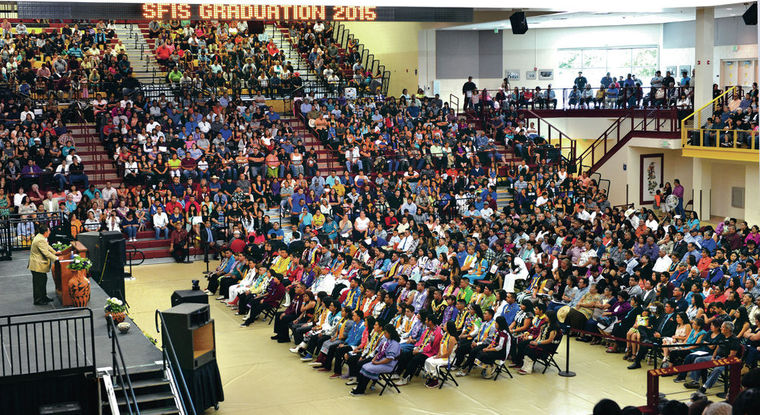

This space encouraged listeners to get out of the deficit mindset when thinking of Native students and give praise to their accomplishments and leadership. These students are in challenging courses, applying to colleges, speaking their languages, taking care of their families, active in honor societies, graduating high school, and remaining grounded in the foundation of their culture as they do so.

The White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education supports positive representations of Native youth from communities all over the country. These young people are the reason behind the mission of the WHIAIANE and have helped to reinforce the country’s responsibility to recognize and educate all of its citizens.

Learn more about Pathkeepers here.